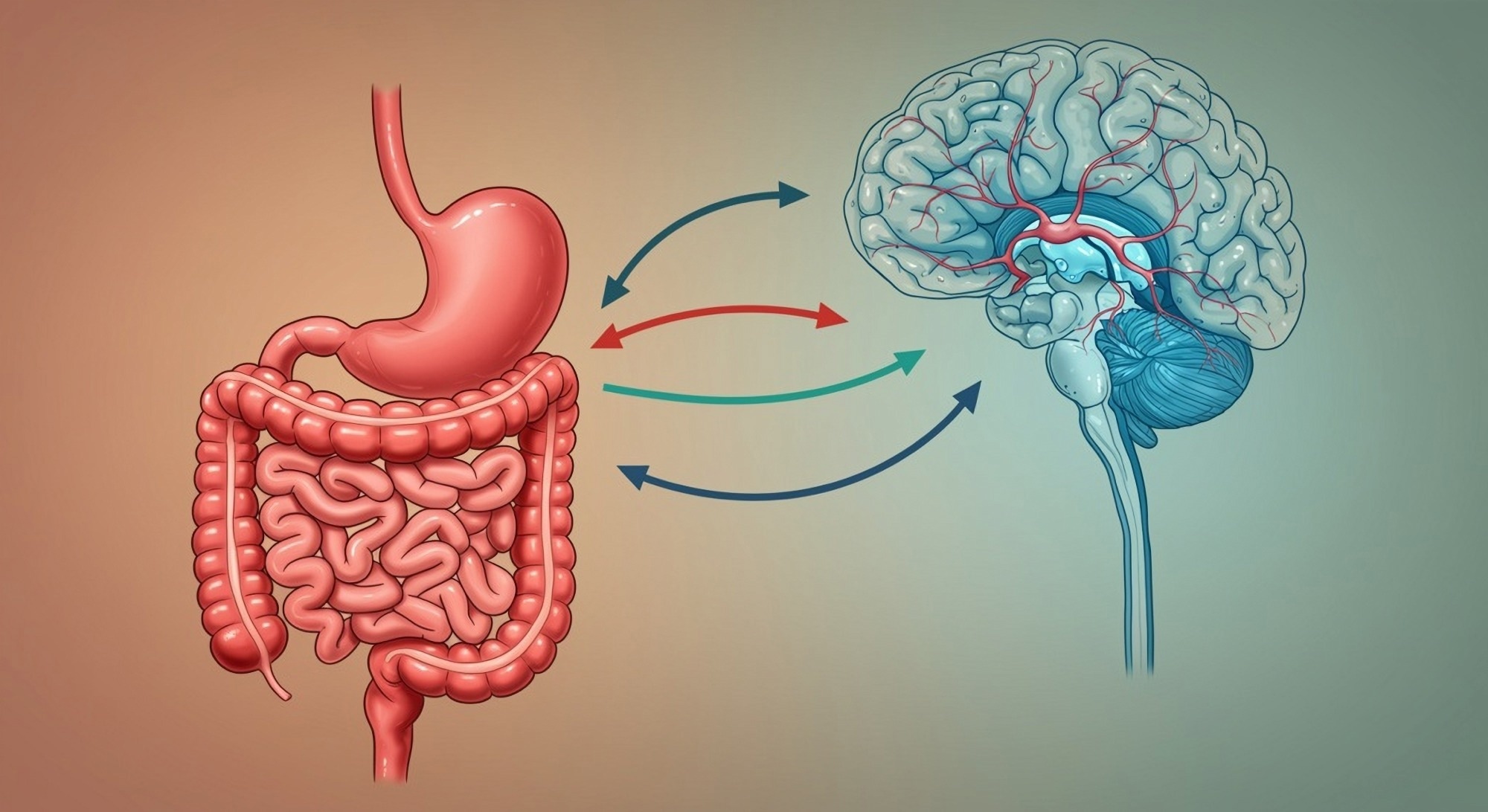

Recent scientific advances have increasingly underscored the critical role gut microbiota plays in overall health. From influencing emotional responses and mental well-being to shaping susceptibility to autoimmune diseases like lupus and type 1 diabetes, the balance of microorganisms in our digestive system is proving to be far more influential than once believed.

A groundbreaking study published in The Journal of Immunology adds to this growing body of research, revealing a potential link between maternal gut microbiota and the development of autism in offspring. The study, led by PhD researcher John Lukens from the University of Virginia School of Medicine, emphasizes that a child’s risk of developing autism may be significantly affected by the composition of their mother’s microbiota—perhaps more so than their own.

“The microbiome is really important to the calibration of how the offspring’s immune system is going to respond to an infection or injury or stress,” said Lukens.

Central to this research is a molecule produced by the immune system called interleukin-17a (IL-17a). Previously associated with autoimmune conditions such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis, IL-17a plays a dual role: helping the body fend off infections, particularly fungal ones, while also influencing brain development in utero.

https://www.thekeyschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/what-is-autism-spectrum-disorder.png

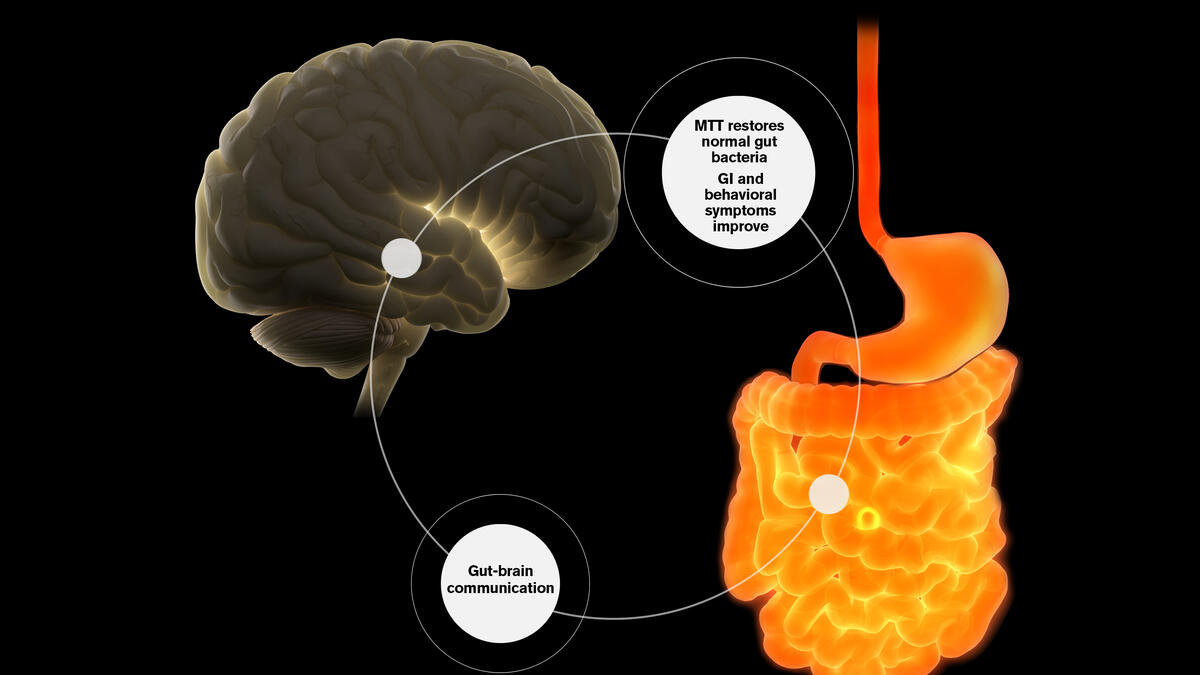

To investigate this connection, researchers conducted experiments using two groups of female lab mice. One group carried gut bacteria that naturally produced inflammatory responses involving IL-17a, while the other did not. When the IL-17a molecule was suppressed in both groups, the offspring of both sets of mothers exhibited typical social and behavioral patterns.

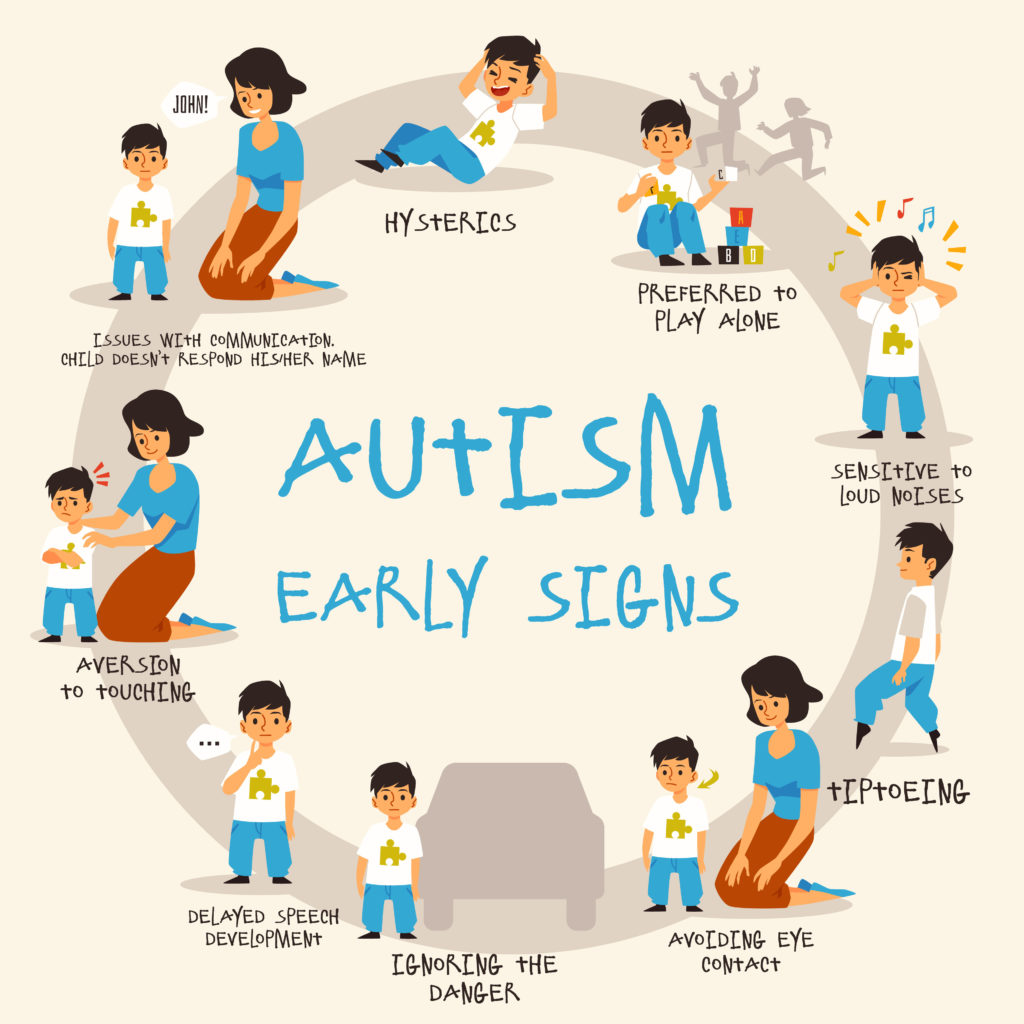

However, without intervention, the offspring of the first group—those exposed to inflammation-inducing microbiota—developed behavioral traits akin to autism, including deficits in social interaction and repetitive behaviors.

To further confirm this effect, scientists performed fecal microbiota transplants from the first group into the second, effectively transferring the microbiome profile. The result: the second group’s offspring began displaying similar neurological traits, strongly suggesting that the altered gut flora—rather than genetics alone—was influencing brain development.

Though these findings are based on animal studies and may not directly translate to humans, they offer a significant insight into the role of maternal gut health in early brain development and the potential for neurodevelopmental disorders like autism.

Lukens emphasized the complexity of this connection, noting that IL-17a might only be one piece of a larger puzzle. Future research will aim to identify which specific components of the maternal microbiome are most closely associated with autism, and whether these patterns are observable in human populations.

Source: The Journal of Immunology